The Friction We Keep

If writing is a technology for thinking, what happens to the thinking when the writing gets automated? An essay on fountain pens, artificial intelligence, and the friction worth keeping.

Somewhere in the last two years, writing became effortless. You describe what you want, and language appears: coherent, grammatical, organized, and largely indistinguishable from what a competent human writer might produce on a good day. The latency between thought and text has collapsed. The friction is gone.

I've been thinking about what we lost when that happened.

I teach university writing and have for over fifteen years. I also teach AI-assisted writing, which means I spend a significant portion of my professional life thinking about what large language models are doing to the act of composition. To the drafting, the revision, the struggle, the ownership. I'm not a skeptic of these tools. I use them. I research them. I build pedagogical frameworks around them. But I keep returning to a problem that the tools themselves can't answer: if writing is a technology for thinking, what happens to the thinking when the writing gets automated?

This is not a new question. It has ancestors. When Plato worried that writing itself would weaken human memory, he was asking a version of it. When scribes gave way to the printing press, someone was asking it. When typewriters replaced longhand, when word processors replaced typewriters, when spell-check arrived and then autocomplete, each transition produced its own version of the same anxiety. We adapted each time. We'll adapt again.

But adaptation isn't the same as resolution. Something changes at each transition, and not always in ways we fully account for until much later. The question worth asking right now, before the adaptation is complete, while we're still in the middle of the contact zone, is what exactly is changing and whether we have any say in how it goes.

I picked up a fountain pen in the middle of all this. I want to be precise about why, because it wasn't sentiment. It wasn't a retreat. I'm not interested in analog tools as a rebuke to digital ones, or as evidence of some superior authenticity that handwriting possesses and keyboards don't. That argument bores me. It's nostalgic in the worst sense. It mistakes the container for the content.

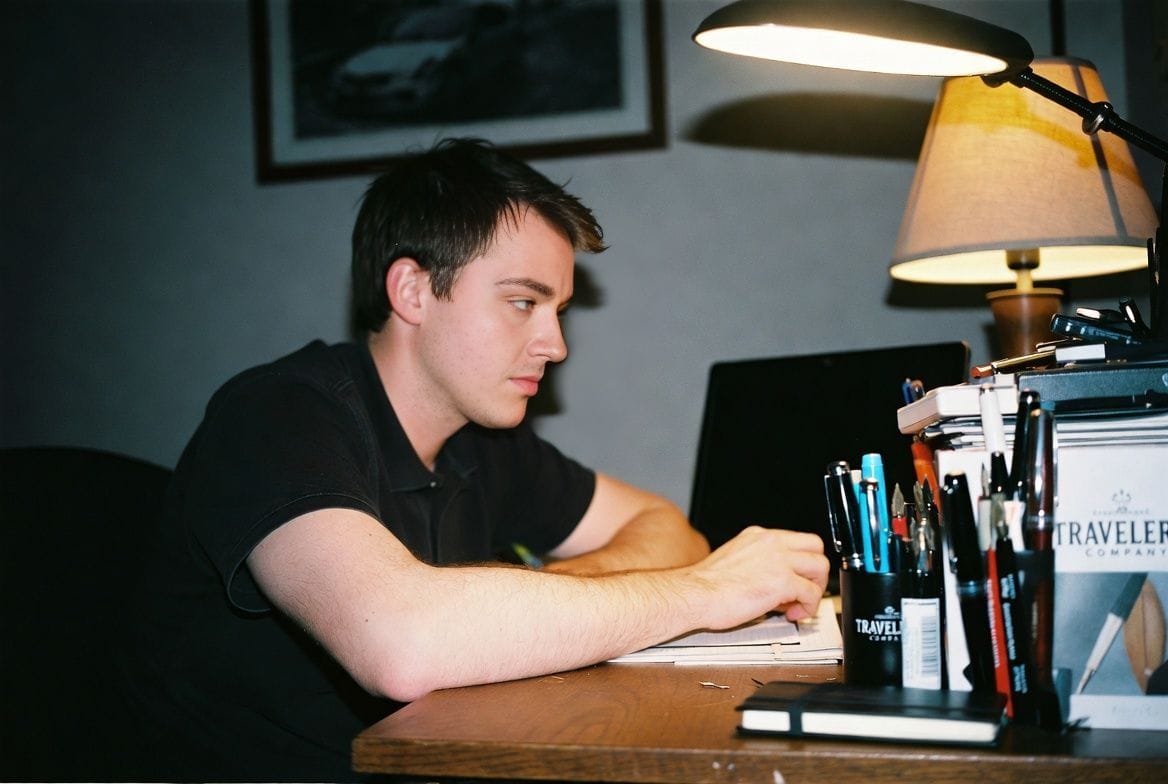

What interested me was something more specific. When I write with a fountain pen, with a particular nib, on a particular paper, with an ink that moves in a particular way, I write differently. Not better, necessarily. Differently. The hand slows. The line of thought slows with it. Sentences that would have unspooled automatically through a keyboard instead arrive with a little more deliberation, a little more weight. The instrument is doing something to the cognition. That's not mysticism. That's rhetoric: the study of how the medium shapes the message, how the tool shapes the thought.

The fountain pen is an extreme case of a general truth. All writing tools are arguments about what writing is for. The AI writing assistant argues that writing is primarily a product, something to be generated efficiently and evaluated on its outputs. The fountain pen argues that writing is primarily a practice, something to be inhabited, refined, felt in the hand. Neither argument is entirely right. But we are living in a moment when one of them is very loudly winning, and I think it's worth paying careful attention to what the other one still has to say.

This is what Analog Proof is for. Not to romanticize the pen, not to resist the algorithm, but to read the contact zone carefully. To look at the tools that slow us down and ask what the slowness is doing. To talk to the people who make ink and grind nibs and choose paper weights with the kind of deliberate attention that feels almost countercultural right now. To take seriously the possibility that friction is not a problem to be solved but a feature to be understood.

The history of analog writing tools is also, it turns out, a history of human relationships to thought itself. The instruments we choose to write with tell us something about what we believe writing is: what it costs, what it produces, what it's worth. In an age when that cost is approaching zero and the production is approaching infinite, those questions feel more urgent than they have in a long time.

I don't have a clean answer to any of this. I'm not sure a clean answer is the right thing to want. What I have is a practice, ink on paper, nib on page, and a set of questions it keeps generating. What does it mean to write slowly on purpose? What do we preserve when we preserve the friction? What are we actually automating when we automate the words?

I'd like to think through those questions here, in public, with anyone willing to think alongside me.

What do you think we lose when writing becomes effortless, and does it matter?